|

July, 2005

Aug. 2005

Sept. 2005

Oct. 2005

Nov. 2005

Dec. 2005

Jan. 2006

Feb. 2006

Mar. 2006

Apr. 2006

May 2006

June 2006

July 2006

August 2006

September 2006

October 2006

November 2006

December 2006

January 2007

February 2007

March 2007

April 2007

May 2007

June 2007

July 2007

August 2007

September 2007

October 2007

November 2007

December 2007

February 2008

March 2008

April 2008

May 2008

June 2008

July 2008

August 2008

September 2008

October 2008

November 2008

December 2008

February 2009

March 2009

April 2009

May 2009

July 2009

August 2009

September 2009

November 2009

December 2009

January 2010

February 2010

March 2010

April 2010

May 2010

June 2010

July 2010

September 2010

October 2010

November 2010

December 2010

January 2011

February 2011

March 2011

ČERVENÁ BARVA PRESS NEWSLETTER

Gloria Mindock, Editor Issue No. 65 April, 2011

INDEX

Cervena Barva Press Celebrates 6 years!

Wow! Time has flown. The press has done so much in these 6 years.

In April, 2005, Červená Barva Press published 21 poetry postcards from 20 poets.

From 2006-2010, the press has published 61 chapbooks and 23 full-length books.

So far, in 2011, we have published a poetry book and 2 novels.

This month, you will see the release of 2 chapbooks and 5 full-length books. The books are on the last stages before printing.

This is exciting! We have many more books scheduled to come out the rest of the year. As you can tell, Červená Barva Press is

very active in publishing. Bill and I would like to thank everyone for making Červená Barva Press thrive. We would not be in

existence without you!

On April 15th, the Pierre Menard Gallery is closing its doors.

I would like to thank John Wronoski for giving Červená Barva Press a

home for its reading series these past years.

John gave so much to the community in the area and many writers and presses used his gallery for their readings. I think we lost one

of the best places to read in the area. So John, thank you, for the wonderful exhibitions at the gallery, Lame Duck Books, and a cozy

wonderful space to have readings. You are the best!

April, is our month for fundraising.

So dig out your credit card or checkbook and please help Červená Barva Press by ordering a

book or two, a chapbook, or donate some money. Every cent we make goes into publishing our books. When you look at how many books

we publish, this shows that we need your help!

You can donate online at:

http://www.cervenabarvapress.com/fundraising.htm

Happy National Poetry Month! April is a busy month celebrating poetry. Be sure to check out the poetry readings and events in your

area. There is so much happening.

Check out our Readings page. Maybe you'll find a listing there. We list readings from all over the country

when they are sent to us.

We will be adding 22 books to the store from various authors and presses on consignment within the next two weeks so be sure

to check them out.

For those of you who already have books in

The Lost Bookshelf on consignment, you might consider discounting your

books especially if they haven't sold. No one wants to pay full price for a book that has been out for awhile when

they can get it cheaper on Amazon or at other bookstores. Please rethink your cost. We still will be taking 30% which

is really good compared to most bookstores. If you decide to discount your books, please e-mail me and let me know.

Allow a few weeks for the Webmaster to make these changes.

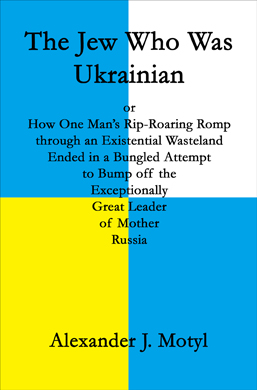

Červená Barva Press Announces a New Book of Fiction

from Alexander J. Motyl

The Jew Who Was Ukrainian

or

How One Man’s Rip-Roaring Romp

through an Existential Wasteland

Ended in a Bungled Attempt

to Bump off the

Exceptionally

Great Leader

of Mother

Russia

Alexander J. Motyl (b. 1953, New York) is a writer, painter, and professor. He is the author of four novels,

Whiskey Priest, Who Killed Andrei Warhol, Flippancy, and The Jew Who Was Ukrainian; his poems have appeared in

Counterexample Poetics, Istanbul Literary Review, Orion Headless, The Battered Suitcase, Red River Review, and New York Quarterly.

Motyl’s artwork has been exhibited in solo and group shows in New York, Philadelphia, and Toronto. He teaches at

Rutgers University-Newark and lives in New York.

The Jew Who Was Ukrainian is a devilishly witty intellectual farce in which historical meditation faces off with madcap

lampoons of past and present political rogues and assassins. Motyl’s wildly imaginative riff on a century of East European

history is a must read. The Moral of the Popcorn reigns!

—Catharine Theimer Nepomnyashchy

Ann Whitney Olin Professor of Russian Literature, Barnard College

Only Alexander Motyl could conjure up this delightful mixture of ghoulish, existential

madcappery with insightful, satirical brilliance. This is a fantasy for the adventuresome,

geopolitical reader who’s eager to have his mind bent and tickled.

—Jed Feuer

Composer, New York City

This hilarious and poignant anti-historical novel is a vertiginous journey through the

Russian Revolution, Stalin’s purges, Nazi concentration camps, underground anarchist

gatherings, and the KGB network. A great master of tragicomedy, Alexander Motyl

shows with eminent irony that twentieth-century history was funnier than Joyce

imagined and much more horrible than Orwell prefigured. His main character, the

laughable Volodymyr Frauenzimmer, works through his excruciating guilt, split hence

irreconcilable identity, and obfuscating desire to settle accounts with history. Pondering

the question of whether to kill or not to kill the next Russian dictator, Volodymyr

transcends the border of the real and enters a realm where infamous political terrorists

and their famous victims come together to discuss the self-destructive power of hatred.

This book is a cold shower for anybody who still thinks you can change history and

passionate encouragement for all those confident that you can do nothing about it.

—Yohanan Petrovsky-Shtern

Associate Professor in Jewish History, Northwestern University

Candide meets The Terminator—in the funhouse of history, ethnic prejudice, ethics…

and the dysfunctional family. An intellectual thriller (camps and assassins included).

—George G. Grabowicz

Professor of Ukrainian Literature, Harvard University

Alexander Motyl is a master of seduction by the preposterous.

—Myrna Kostash

Writer, Edmonton, Canada

$16.00 | ISBN: 978-0-9831041-1-7 | 181 Pages | Fiction

Shipping Costs:

For 1 book is $4.25 Domestic or $7.00 International

Domestic: $16.00 + $4.25 = $20.25

International: $16.00 + $7.00 = $23.00

Order by mail:

Send check or money order payable to: Červená Barva Press

P.O. Box 440357,

W. Somerville, MA 02144-3222

The Jew Who Was Ukrainian Book launch at the Ukrainian Museum

The Ukrainian Museum

222 East 6th Street

btw 2nd and 3rd Avenues

New York, NY 10003

Copies of The Jew who was Ukrainian will be available for sale during the launch, and the author will be on hand for the

book signing. Tickets: $5, which includes a reception, may be purchased online or at the door.

http://www.ukrainianmuseum.org/shop/display.php?cat=26

Book presentation

Ukrainian Institute of America

2 East 79th

Street · New York, NY 10075

Saturday, April 16, 2011, 7:30pm.

For more details, see:

http://www.ukrainianinstitute.org/events.php?date=2011-04-16

Other book launches will be at St. Vladimir's Institute in Toronto and at The

Ukrainian League in Philadelphia. Dates to be announced shortly.

Interviewed this month: William Walsh by Scott Roberts (Scroll down)

Come join us at...

THE FIRST AND LAST WORD POETRY SERIES

Hosted by: Harris Gardner and Gloria Mindock

THE CENTER FOR THE ARTS AT THE ARMORY

POETRY AT THE CAFÉ

191 HIGHLAND AVENUE

SOMERVILLE, MA

TUESDAY, APRIL 12TH

6:30 PM /ADMISSION: $4.00

READING AND OPEN MIC

Joshua Coben's first book, Maker of Shadows (Texas Review Press, 2010), won the X.J. Kennedy Poetry Prize.

His poems have appeared in Atlanta Review, Pleiades, Poet Lore, and other journals. A St. Louis native, he

lived in France for two years before moving to Boston. He teaches elementary school and now lives in Dedham

with his wife and three children.

Ron Slate's first book of poems, The Incentive of the Maggot (2005), was nominated for a National Book Critics

Circle prize, and was followed by The Great Wave (2009). He spent thirty years working in business, and was

vice president of global communications for EMC Corporation. He reviews books at a blog called "On the Seawall"

and is writing a novel titled Out of Pocket.

Kim Triedman won the 2008 Main Street Rag Chapbook Competition for her first collection "bathe in it or sleep" and

has also won and placed in numerous other poetry and fiction competitions. She was recently nominated for Best New

Poets 2009 and Best of the Web 2010. This past year she edited Poets for Haiti: An Anthology of Poetry and Art

(Yileen Press), which benefits Partners in Health. She is a graduate of Brown University.

The Center for the Arts is located between Davis Square and Union Square. Parking is located behind the

armory at the rear of the building. Arts at the Armory is approximately a 15 minute walk from Davis Square

which is on the MTBA Red Line. You can also find us by using either the MBTA RT 88 and RT 90 bus that can be

caught either at Lechmere (Green Line) or Davis Square (Red Line). Get off at the Highland Avenue and Lowell

Street stop. You can also get to us from Sullivan Square (Orange Line) by using the MBTA RT 90 bus. Get off

at the Highland Avenue and Benton Road stop.

Women’s Words Writers Workshop

Kinnicut Hall, Room 115

Worcester Polytechnic Institute

Worcester, MA

Salisbury Labs; 8:00am-3:30pm

Saturday, April 30, 2011

A Fundraiser for Daybreak (Domestic Violence Prevention Programs)

Sponsored by Worcester Polytechnic Institute and the YWCA Worcester

Chaired by James Dempsey, Administrator of Literary Studies at WPI

8:00am Registration and Continental Breakfast / Salisbury Labs, 1st floor Lounge

8:30am Welcome and Opening Remarks

8:45am Children’s Literature: Vicki Ethier & April Jones/Salisbury Labs 104

8:45am Nonfiction: Eve Rifkah & S. J. Wolfe/ Salisbury Labs 105

9:45am Memoir: Lora Brueck & Susan Rako/ Salisbury Labs 104

9:45am Fiction: Jan Brogan & Judy Jaeger / Salisbury Labs 105

10:45 am Break

11:00am Poetry: Mary Bonina & Eve Rifkah / Salisbury Labs 104

11:00am Journalism: Janice Harvey & Diane Williamson /Salisbury Labs 105

Noon Lunch signing for authors leaving early

Noon Lunch

1:00pm Writing Workshops

(3 tracks, 90 minutes each)

Poetry Workshop: Mary Bonina

Non Fiction: Susan Rako

Fiction: Kimberly Newton Fusco (confirmed)

2:30pm Publishing Resources

Claire Golding (confirmed)

Author and Freelance Writer/Editor at

Salamander Crossing Editorial Services

Trish Wooldridge (confirmed)

Broad Universe

Tom Campbell (confirmed)

King Printing

Noah Bombard

Critter Publications (contacted)

Lynn Riley (resource)

WPI Research and Instruction Librarian

3:45 pm Closing remarks followed by book signing and signing of contact list for attendees.

Attendees are being asked to pay a $55.00 registration fee for the conference which will include continental breakfast and lunch.

Students can register for $25.00.

Attendees can register and pay on line at http://www.ywcacentralmass.org/2011/05/05.

WONDERBENDER by Diane Wald

1913 Press, 2011

ISBN: 978-0-9779351-8-5

$11.00

Pages: 83

To order: www.1913press.org

"Diane Wald is a sensational poet in the best meaning of the word-sensation as the true source of wisdom. These poems confide

and entice, whisper, and dare; they are inviting for their passion and astounding for their prescience. I can think of no poet

who can be so imaginative and intimate at once. Frost said the poem begins in delight and ends in wisdom, and Wonderbender is

rife with both virtues."

-John Skoyles

Mississippi Poems by Linda Larson

ISCS Press, 2011

ISBN: 978-0-98227115-2-1

$12.00

Pages: 63

To order: www.iscspress.com

"Linda Larson is an accomplished poet who has her eye to the sky and the street-and

she writes poetry that you will remember."

-Doug Holder/Ibbetson Street

TWO BLOODS, fly fishing poems by Gary Metras

Winner of the 2010 Split Oak Press Chapbook Award

Spilt Oak Press, 2011

ISBN: 978-0-9827521-2-8

$14.00

Pages: 45

To order: www.splitoakpress.com

"Two Bloods richly evokes the life of rivers and their trout, and also the spirit of a wise poet whose blood mingles with

the life of both as he fly fishes. These are supberb poems. They can stand proudly beside those of Richard Eberhardt,

John Engles, and Ted Hughes."

-Nick Lyones, author of The Seasonable Angler

Insane in the Quatrain by Bradley Lastname

the press of the third mind, 2011, Chicago, Illinois

Pages: 189

$10.00

To order: www.bradleylastname.com

For information, check out the press or link provided.

Keeping the Wolves Off the Front Porch

An Interview with William Walsh

by Scott Roberts

Scott Roberts works at Atlanta magazine as a copy editor/writer. He is a regular contributor of CD and concert reviews to

Atlanta Music Guide. In addition to William Walsh, Roberts has also interviewed Amy Ray (Indigo Girls), Richard Lloyd (Television),

Steve Wynn (Dream Syndicate), and Fran Healy (Travis). He is also an accomplished singer/songwriter/guitarist whose band,

Last Chance Runaround, performs regularly in Atlanta and beyond in support of their 2010 debut album Alter Idem.

The list of literary interviews by William Walsh reads like a who's who of genius: Czeslaw Milosz, Joseph Brodsky, A.R. Ammons,

Doris Betts, Shirley Ann Grau, Pat Conroy, Harry Crews, Pearl Cleage, Ariel Dorfman, Mark Doty, Elizabeth Spires, Eamon Grennan,

Edward P. Jones, Fred Chappell, Rita Dove, Donald Justice, Kate Daniels, Madison Jones, Lee Smith, Miller Williams, Andrew Lytle,

Ursula LeGuin, Madison Smartt Bell, and many more. For more than twenty-five years, he has crafted a style of interviewing that

has entrusted himself as a well-respected curator of the modern writer. Per the American Studies at Cambridge University Press,

"His interviews are remarkably direct and to the point. . . each [interview] has a strong sense of its place and time. . . ."

It is with such style and grace that he has gained access to some of the world's finest writers.

Born in Jamestown, NY, Walsh has degrees from Georgia State University and Vermont College of Norwich University (M.F.A. 1991),

and is currently pursuing a Ph.D. at Georgia State. His books include Speak So I Shall Know Thee: Interviews with Southern Writers

(McFarland), The Ordinary Life of a Sculptor (Sandstone), The Conscience of My Other Being (Cherokee),

Under the Rock Umbrella: Contemporary American Poets from 1951 to 1977 (Mercer University Press), and

published in 2010, David Bottoms: Critical Essays and Interviews (McFarland). His interviews and poetry

have been published in The Kenyon Review, Five Points, the North American Review, Poets & Writers,

Michigan Quarterly Review, Hunger Mountain, and Verse. He is a internationally recognized photographer

and is one of the team photographers for the Atlanta Silverbacks professional soccer team. This interview

was conducted in Atlanta, GA as we sat outside a local Starbucks.

ROBERTS: Did you write as a child and when did you know you wanted to be a writer?

WALSH: The earliest I remember, probably in the second grade, I wanted to be a writer, and I recall late at night in bed

thinking up stories, wondering about the universe and what was out there beyond space, beyond God, beyond whatever God was-an

idea that, looking back, is relatively sophisticated for a young boy. But, to be a writer, you had to be smart, and as a kid

I never thought I was smart because I didn't make good grades in school. I tried very hard - I just failed to make good grades.

The interesting thing about being a writer is the requirement, the necessity, to sit still for long periods of time to be creative.

Well, I have ADHD, which is not a great combination if you want to be a writer. We found this out when my boys and my daughter

were diagnosed with ADHD. I'm the quintessential poster child for the inability to sit still. I always need a project to be

working on. I know now that ADHD was the primary reason I made poor grades in school, but at the time, no one knew this.

I was tested for disabilities and it was determined nothing was wrong with me and that I should have been making As. But,

no one figured it out. Truth be told, I was bored most of the time, but saying so was sacrilegious. If I was bored, it

couldn't possibly be the teacher's fault-the authority figure-so it became my shortcoming. I was told simply to try harder

or that I wasn't applying myself. So it was extremely frustrating. Here I was playing chess at age four and defeating my

father by seven, but I would study and study and still make Cs. As a result, I didn't think I could be a writer. However,

in the 7th grade I had a teacher, Kathy Collier (nee Sims), at Vivian Field Junior High in Farmers Branch, Texas, and as an

exercise, the class wrote short stories and poems. She was simply the greatest teacher I had ever had-just wonderful. The

flood gates opened and I took it upon myself to write every day. I remember standing out among everybody, and not to sound

braggadocios, but I knew it. Hell, when you're not good at anything in the entire world except playing baseball, being the class

clown, and making Cs and Ds, it felt pretty good to have the teacher praise you.

ROBERTS: Were you the athlete type because you're very athletic anyway?

WALSH: I was very athletic and sort of saw my self as a kid who could play any sport and play it well. I still play competitive

tennis and golf. A few years ago I shot a 68 in a golf tournament. I almost made a hole-in-one on a par 4, 335 yard hole - I

missed by 18 inches. If I play a lot, I can shoot in the 70s, but I'm not going on tour any time soon. I don't love golf that

much to play five times a week. I've played golf with Billy Andrade, Allen Doyle, and Kathy Whitworth, and a bunch of other pros,

just in fun rounds of golf, but primarily, I like playing in charity golf tournaments to raise money for a good cause especially

if my friends join me. We have a blast. I still play competitive tennis and can still play against some college players, but it's

more and more difficult as I get older-injuries. The body simply starts breaking down, and after a long match, the recovery time for

me is several days, coupled with a lot of Advil. But I still have my moments.

As a kid, baseball was my sport, and from early on I understood all aspects of the game, even at seven-years-old - I simply

understood the science of the game. I still remember my first baseball practice that my father took me to when I was eight

while living in Fairview, PA. The coach was very nice man, John Rapp, and while taking grounders, a sharp ball was hit up the

middle to his son, Chip, who missed the ball when it hit a rut of grass and bounced over his shoulder, but there I was about

ten feet behind him backing him up and snagging the ball. No one told me to do this-it was instinctual. Baseball was really

the only thing, as a child, I was good at. It's all I wanted to do and all I thought about 24/7. There were times when I would

stand in my grandfather's front yard with a baseball bat and for hours hit fallen apples across the street and into a field.

Interestingly, all my heroes were black baseball players: Roberto Clemente, Bob Gibson, Willie Stargell, Al Oliver, Hank Aaron,

and of course, my hero of heroes was Roy White, the left fielder for the Yankees. And, I played, of course, left field. Shortstop,

too. I really thought one day they would drive by the house and see me hitting apples and get out and play catch with me. Then at

age 11 I started playing soccer. In the eleventh grade I tried out for a minor league soccer team, but when I was offered a position

on the team my father objected, saying that I could not forgo school to travel around the country playing soccer. He was right,

of course. Most importantly, I probably was not (and never have been) mature enough for the role of a professional athlete.

ROBERTS: Was it important to receive encouragement, thinking you could be writer?

WALSH: It was tremendously important. I don't think I'd been praised by any teacher for anything academically, and when

Mrs. Collier praised me, I wanted nothing more than to please her in return more so. Truthfully, I never pleased any of my

teachers in any academic situation except gym class. Everything else was a huge strain. I made one A in high school in a senior

English class when I was a sophomore. I had just moved, yet again, to another state and with only six weeks of school remaining,

there was nothing the school could offer me, so they stuck me in a class with seniors. The counselor actually warned me that I was

likely to fail but he had no choice. Well, the teacher looked like John Lennon and all we studied was American fiction. Essentially,

for six weeks John Lennon was my English teacher and that was the coolest thing in the world. I never have tested well, either.

In college, when I was preparing for graduate school I took the graduate exam, having studied for months, but I did horribly. It

was embarrassing. Ironically, I made good grades in college and had at one time a 4.0 gpa. I was on the Honor Roll, Dean's List,

all sorts of scholastic merits, really accomplishing something in an academic environment. The powers to be suggested that I take

a graduate exam study course offered by the university to help students score higher. I took this study course for a few months

then I took the graduate exam again and did worse than the first time. These failures have probably contributed to me not

attempting to secure an academic position because someone will probably require me to take a test.

When I was a kid we had three sets of encyclopedias that my dad at some point bought from a door-to-door salesman, and I would

sit at home reading these encyclopedias for knowledge because I wasn't getting anything at school. Looking back on it now, I

realize a conventional school environment probably wasn't the answer for me. But who knew? My parents didn't have the money to

send me elsewhere. Things are different now and my children are enrolled in a very good private school where they have wonderful

teachers. My oldest son, Jon, just tested in the top 1% in the country for his verbal skills. Of course, that made my wife and I

feel great, as well as brought confidence to him.

ROBERTS: Did you enjoy making up stories?

WALSH: I did because it was a form of sanctioned lying. With writing, I could make stuff up and no matter what I made up, it wasn't wrong.

However, being a writer was as foreign as going to Mars. But in the 7th grade I realized I could write. Unfortunately, that summer

we moved from Dallas to Chicago. I wrote a little bit there but less so because my teachers did not encourage it as much. My parents

were avid readers, but I was not - I just couldn't sit still long enough to read a book on a regular basis. I would read the newspaper

everyday and encyclopedias. That was it. In English class in the 8th grade, Miss Novelli, who was from El Paso, let me read anything

I wanted so I chose biographies of Mickey Mantle, Babe Ruth, and Willie Mays. I had to read at least one novel for her class, but I

couldn't do it. I read the first page and thought, "This isn't real. This is fake!" Of course, it never dawned on me that tv was fake!

In class we had these little pow-wows where she asked us to discuss our books and I sat there fabricating the entire novel right before

her, making up some elaborate story. I'm certain she knew it wasn't the storyline, but she never said anything. So, if Miss Novelli is

reading this interview, I apologize thirty years later.

My writing sojourn kind of evolved in that manner. I wrote a little bit in high school, but it wasn't until I college that I really

began writing. Every student was on a level ground where it didn't matter how smart you were, what your grades were in high school,

where you came from, if you had a lot of friends-it was like stepping onto a new continent where everything's based upon your merit

from that point onward. I really understood that. So I started writing. I went a little over board at times - in freshmen composition

class when everyone else was writing a five-page paper, I wrote a 40-page paper on the Beatles.

ROBERTS: Was it a biography on The Beatles?

WALSH: This sounds silly now, but I tried proving that Paul McCartney had died and was replaced with an imposter. You know

that old rumor, "Paul is Dead." As a writing and research project, it was an absolute blast, especially for a kid who was

project-oriented. It was called This Bird Has Flown. Literally, I studied every aspect of the Beatles. I took their albums

downtown to a recording studio and had them recorded backwards, slowed down, sped up, and had all sorts of things manipulated

then I listened to these recordings over and over searching for clues.

ROBERTS: Do you still have that paper?

WALSH: I may have shredded it. It's not something I would ever publish. I received an A for the paper. The teacher,

Dr. Waller, was fascinated by the evidence I had compiled - not only evidence other people had discovered but what I discovered

on my own. I interviewed people. There was a professor in Miami who had conducted a voice analysis of Paul McCartney's singing

voice "pre death" and then "post death" (some time in 1966) for the differences in the actual voices of the two individuals. If

I remember correctly, he determined there was a difference in the voices, two different singers.

ROBERTS: What was your conclusion?

WALSH: At the time I thought that McCartney probably died in 1966 and was replaced by a man named William Campbell, who was a

split-image of McCartney. See, Billy Shears from Sgt. Peppers Lonely Hearts Club Band. Billy - William. Shears, the cutting

of old ties. Stuff like that. I was quite naive to believe all that. I studied ancient burial rituals, different religions and

ideas, and read the Tibetan Book of the Dead since it reportedly had influenced John Lennon. But each new clue was monumental,

like searching for the Holy Grail. None of it matters now, but at the time, I thought this was the greatest mystery since Kennedy's

assassination.

ROBERTS: What did you study in graduate school?

WALSH: Poetry. I could have gone to law school because it's one of the few things I've ever tested well for, and my wife is an

attorney and I have a very law-oriented mental process rattling around in my head, but I chose poetry. Of course, I would never

have passed the bar exam! I earned a Master of Fine Arts degree at Vermont College where I studied with Jack Myers, David Wojahn,

and Susan Mitchell for my primary core study, and then I to some degree with Mark Doty, Linda Hull, and Mark Cox. I absolutely

loved it. There were some very talented student writers - David Mura, who graduated the semester before me and had already won a

National Poetry Series award. We had classes together. Mature poets such as Tim Seibles and Frank Paino were there at the same

time, and having peers like them pushed me to step up very quickly. I understood how good my peers were. When I graduated from

Vermont, I felt that I was the best poet in my class - not arrogantly - but I just felt that I had become a poet and no one was

writing what I was.

ROBERTS: Everybody always wonders what you can do with an English degree, but there are even more limitation for a masters

in poetry.

WALSH: No, absolutely not. It's the opposite. I've had many doors open up because of my advanced degree, albeit not always in

the academic world, per se, but even in academia. The door swings open pretty wide at times. But, even with an advanced degree

I've had every rotten-ass job that's out there, make no mistake. There are a lot of PhD grads working at Starbucks. I have worked

with some of the biggest morons a person could ever work with and I have tolerated many rotten jobs just so I could leave that job

behind, come home, and write. I chose to write poetry. I could have been an attorney or a ditch digger, but free will led me to

write poetry as well as teach poetry, which I enjoy almost more than anything else in the world.

ROBERTS: How did you deal with being educated and working rotten jobs and writing?

WALSH: At times it was degrading. Being educated and working with a bunch of idiots is never any fun, but I got through it.

There's very little money in writing poetry, but that was never the reason for it. And, of course, I do not make my living at it.

I am a private investigator and run my own company trying to combat fraud. I'm also a fairly decent photographer. However,

when you work shit jobs year after year in order to write, to peruse your dream, it begins to weigh heavily upon you, especially

when you are not getting published. I had these rotten jobs up until 15 years ago when I started my own company. These rotten-ass

jobs allowed me to write all day long and then off I went to a job that was relatively mindless. I worked in the computer industry,

8 to 12 hours a day in an operational capacity. I reprogrammed things to run faster and run more efficiently and once I did that,

most of my work was done in about four hours. I worked alone for the most part then was able to sit there reading or editing an

interview or working on a poem. As long as the computer system didn't blow up, the boss left me alone. Then I'd go home and not

care if the company went under, just as long as it didn't happen while I was running the show. But, I struggled for years and

couldn't get anything published. Absolutely nothing.

ROBERTS: Were you getting rejection letters?

WALSH: They showed up in the mail like past due notices. Sometimes I'd get a nice note back from an editor and that kept me going

somewhat. It wouldn't always be a long letter, maybe just a hand-written note, but at least my poem made it through the slush pile

and into their hands. Still, it was difficult. It is for all writers - that's why you cannot give up. As a writer you must persevere.

I am always telling my children and students that old cliché: Winners never quit and quitters never win. It is absolutely a

scientific fact, like gravity.

A friend of mine is Don Johnson, not the actor, but the former #1 doubles player in the world. He's beaten Sampras,

Federer, many of great players. Don won Wimbledon men's and mixed doubles, and scores of other tournaments. He was a U.S.

Open Finalist. Years ago he was struggling to make it on tour and about to give up when he bought a grad prep study guide

for business school. He realized his future was probably no longer going to be as a professional tennis player and traveling

all over the world. If this tournament did not go well, his career was most likely over right there in Mexico City. So here

he was at the Mexico Open playing in the first round against the #1 doubles team in the world with match point against him and

his partner, Francisco Montana, when Don cranked a service return out of the stadium. Whack! - the service return is literally

headed toward the stands when a gust of wind blew the ball back and it landed on the line. He and Montana saved match point

then went on to win that match. They ended up winning the entire tournament, defeating Nicolás Pereira and Emilo Sanchez, 6-2,

6-4 in the finals. All of a sudden they could play any tournament they wanted and started getting invitations to play in the

major tournaments. Several years later Don became the #1 doubles player in the entire world. Think about that. The best in

the world. That's amazing. And to think he was one point away from ending his career. That, to me, is one of the greatest

stories to illustrate my point. You simply do not give up.

ROBERTS: How important is an editor to you, especially with literary magazines?

WALSH: I put tremendous stock in their opinion. If an editor will tell me the problem I can fix it. Most editors and agents,

despite the fact that you feel like they are your enemy, want nothing more than to publish the best material they can, but 99% of

everything that comes in the door gets is returned. Remember, there is no conspiracy against talent, but the odds are staggering,

but so is becoming the #1 doubles player in the world.

By far, one of the best poetry editors I have had is Leon Stokesbury at Georgia State University. He can read a poem! And,

he gets to the heart of the problem quickly. Years ago, I sent a 30-page poem to Marilyn Hacker at The Kenyan Review when she

was the poetry editor. That's a long poem, and, of course, by virtue of its length, I thought it was the next "Love Song for

J. Alfred Prufrock." She wrote back saying it was just way too long. Well, what does Marilyn Hacker know, right? I tossed

the poem in a drawer for about eight years then one day driving somewhere it dawned on me - she was absolutely right - it was

way too long. I rushed home and for three hours edited the poem to eight pages. Now, it had to brilliant, right? Still, it

took me another three or four years to realize that it was still too long. One day I gave myself an exercise - cut the poem

down to 500 words. I worked on it for a few more months. My point to all of this, thirteen years later, Marilyn Hacker, being

an editor, knew her stuff. The truth of the matter is this: each day editors walk into their office with the hopes of finding a

brilliant poem, short story, or essay. There is not that much good material out there. Certainly not thirty pages long. That

poem, by the way, became an elegy, "The Letter Back Home." This is typical of all my writing. It takes me years to finish even

the simplest poem as it's a very slow process, even if to discover the perfect word, the last word. I wish I wrote faster, but

I do not, and that's why I write so few poems. I'm always writing and editing, chiseling away at that huge block of stone trying

to discover my Venus.

The Letter Back Home

My world is not my world. I'm back

to the egg; exhausted

from my flight. Fourteen hours

from Montpelier and trying to beat the winter storm

headed my way, I boarded the wrong plane

twice then returned home to a $1300 checking error.

But worse, sadly, I returned

to learn of the death of a man

who was a great influence

on my life. I was out of town

and missed his funeral.

He was my professor, the first

man who brightened my eyes

to the wonders of Coleridge.

Tomorrow is my birthday.

I have nothing

special planned. Exercising

in my living room

where my sofa would be if I owned one.

My body feels sluggish. Three days home

now and the notches

are falling into place. Six months ago

Caroline kicked me out, two suit cases

jammed with wrinkled clothes. Divorce lingers

on the horizon so the girls

live with her. Yesterday, Caroline said

she never wanted to see me

again. I cannot believe

I was so bad.

Your words on this rainy afternoon

warm the house. I'm eating

instant soup, a cup

of coffee, watching Duke basketball.

My dog is praying to his God

that I drop my toast

on the floor. Your current peace of mind

fits you well. Your health, no doubt,

a result of climate. I am miserable. I'm disgusted

with my behavior because I am not a good friend.

I have been wrong about so much

in life. Can I start over

with you? Tonight, I'm drunk

in love over the art

we call children.

Quoting your letter, "I had

a wonderful dream about you

the other night. Made me feel

like we actually spent time together. . . .

God damn you. I miss you, and you don't

write back." Please forgive my behavior

these past thirty years. I hand out heartache

like windshield flyers. Good things

do happen. I've been awarded

a fellowship to study

in Italy. Since being kicked out,

some dark clouds of my mystery

are lifting, but I cannot bear

to cook. Most evenings

I eat dinner at Marie's,

drink hazel nut coffee,

and pick up women since my sex

appeal to my estranged wife

is like putting on a wet bathing suit. Mostly,

I sit in the kitchen with Marcel

Dufour's daughter, Marianne,

writing a paper on the fusion

of painting and poetry. She asks

a mouthful of questions. Sometimes,

I make up stories to please her imagination.

Marcel lets me wait tables when the women are single.

There is no great energy within me, and I have been failing

to teach my students very well. Such energy

in their misunderstood childhoods

but I can not lift a finger to give a damn.

There is a darkness touching my skin

beneath my clothes.

I mourn my professor's death

because I never took the time - made

the effort - to know him

all these years, when

in fact, I could have.

ROBERTS: How so?

WALSH: Well, it's so different for each of us. As Joseph Campbell proclaimed - we must follow our bliss. Of course,

no one can provide the exact blueprint on how to do this. For example, as an undergrad student at Georgia State University,

I studied poetry under David Bottoms, just a wonderful poet and reader of a poem-he has a good eye for the poem. One day in workshop,

David tore my poem apart, not with any meanness, just as an exercise to wade through the rubble. David was always very nice with his

criticism, but I was pretty pissed off because I had yet again written a masterpiece that he somehow failed to grasp!

Now you have to remember, we were sitting in class for five hours of poetry workshop on a Saturday and I'm wound up on coffee,

Skittles, and ADHD. Essentially David said, "This does not work at all; however, I like the first line: 'I remember when you

soaked corn seeds in a coffee can/ and I walked with you through the till of the garden.'" He liked the imagery and the texture

of the language. That's all I needed from him in regard to praise, and so I threw out the entire poem, except that one line,

which for years I kept repeating in my head. Again, driving down the road eighteen years later, having repeated that line in

my head a million times, the whole poem came to me. I drove home, wrote it down, tweaked it for a couple of months. My

inclination was - a poem coming this quickly must not have much merit, but in reality, I'd been working on that poem in my

head for eighteen years. It was the second to last poem considered for the book, and rightfully titled, "Germination."

Germination

I remember when you soaked corn seeds in a coffee can

and I walked with you through the till of the garden

down the narrow rows of cabbage and zucchini

and you reached down for a fist of soil,

squeezed the minerals tight into a ball

then broke it up. You rolled a handful

of seeds between your fingers,

catching one beneath your thumb

and dropping it like a lure

precisely where you aimed.

With the side of your boot you pushed

the seed into darkness.

There is a new family living in your house

and after forty-five years your garden

is gone. The tires crunching on the gravel

driveway are gone, too, and you

no longer stand on the back porch

waving good-bye. But sitting down the street in my car, I think

how nice the house looks painted light green

and maybe they still play croquet in the backyard.

They should have never uprooted your blueberry bushes.

So maybe, one quiet night in late November

when they are away for the holidays,

I'll return and burn their house to the ground.

ROBERTS: Do you picture the reader as you're writing.

WALSH: I never write for anybody other than myself, because figure I don't have an audience and my job is to write something

that brings you to me. Initially, my goal in college was to get laid, and when you're a poet, there is an attraction to that

from some girls. Let's be honest! That goal has not chanced since Adam was tossed out of the Garden. But once you get past

writing love poetry for the girl you want to sleep with, sometimes the real poetry ensues. There are all sorts of obstacles

along the way, of course. These days, I try staying away from the maladies of poets - everybody I know has a phobia or an

addiction or something. That's not my thing.

ROBERTS: It's kind of romantic to be an addict or something - the tortured artist.

WALSH: I don't find much romance in it. I have friends with all sorts of troubles. I try to avoid that as best as I can.

Life is difficult enough without being stoned or drunk or strung-out on whatever self-inflicted misery there is lurking in the

shadows. I like Bob Hicok's approach to it - exercise gets him high. He plays tennis, too. So did Roethke.

ROBERTS: You're a responsible father.

WALSH: Semi-responsible. I get up, go to work, come home, cook, clean, and take care of my kids, as does my wife. I kick the

dog once in a while to let him know I'm the boss. My wife and I work hard at raising our children in the same house, in

same school district. We've been in our house twelve years. For me, that's an anomaly. I mean, I lived in seventeen houses

as kid. I was in six high schools, one for only five months. There in lies the angst of my life! That's what makes you a poet,

perhaps. When The Conscience of My Other Being was described as a "fractured America," the fractured experience of my American

youth - that's pretty accurate. Although I have a lot of friends now, I have only one friend from childhood. He lives in

Indianapolis and I still consider him my best friend. I could call him up this instant and if I needed $20,000 to get out

of jail or leave the country he'd give it to me no questions asked. I would do the same for him, as well as for my two brothers.

That's where I write from, piecing together the experiences, distilling them into the whiskey of life.

Wine if you're more refined.

ROBERTS: Do you find a thread thematically running through your poetry?

WALSH: It's probably the fractured experience, but no, I didn't realize this until it was pointed out to me. Fred Chappell

wrote me a nice letter and pointed something out regarding The Conscience of My Other Being. He said the narrator, the alter

ego, is a smartass. I don't deny that. It's a badge of honor. I enjoy being funny, a kind of smartass who knows there is a

joke being played at your expense. But I make fun of myself, too. I also like the idea of making a person cry or well-up with

emotion if I hit the right chord. Either way, I'm doing my job.

ROBERTS: I like the seriousness of the poems but I really gravitated to the more humorous.

WALSH: I think poetry is a serious business but you can be very serious with humor in poetry. I find a lot of things to be

funny and I like making fun of everything and everyone. Even though I'm telling you something incredibly serious, I might just

be winking at you or pulling the sheets over your eyes, getting ready to whack you with a rubber chicken. It'll hurt but won't

kill you. I do tend to think some of my poems are subversively political. "Bless You" is completely political. No mystery

there. And completely humorous. A friend of mine in China wrote saying my books are banned in China. That's another badge of

honor, but then aren't most books banned in China?

ROBERTS: "Bless You" is very funny but a serious look at the politics of the day.

WALSH: I realized when George Carlin died, and not to compare myself with Carlin because he's brilliant and I am not, but I

like to be funny. You will laugh, but there's so much seriousness behind what you're laughing at that you have to stand back

and say, "How can I laugh at this?" That's how Carlin was, I think. He'd make fun of things that were so serious then you

realize that you are laughing at yourself or society. The first time I read "Bless You" (the entire poem), this ten-page poem,

to an audience in Charlotte, NC at a writer's conference, I realized how funny I was. I thought the poem was a deadly serious

knock against political correctness, but I had to stop every few minutes for the laughter to wane. That was not expected. It was

then I realized something was happening. That week, Kestrel accepted the poem for, I believe, their debut issue.

It's the same way with the novel I have just finished writing, A Weird Girl From Heaven. I've taken on a serious subject - race,

hatred, murder, suppression, and I have at times written very comical elements into the book. But it is not a comedy. Funny things

happen, but it is about the past, a history that is thought to be buried, rising up fifty to one hundred years later and influencing

the current day. How the main character deals with the past in her quiet every day life is extremely exciting to me.

ROBERTS: You used the word alter ego. Are your poems funnier than you or do your friends sort of think of you as the

funny guy, the guy to hang out with at the party?

WALSH: There are times when I'm the guy to hang out with at the party because I am pretty damn funny. You might think I'm never

serious about anything, but that's not true. If I don't know anyone, I'm a wallflower.

ROBERTS: You don't seem like wallflower. The other night you went right up to Don Dixon and said here's who I am. . . .

WALSH: That was business. There was business to be done. I was also hoping his wife, Marti Jones, was there, too. She's been

one of my favorite singer/songwriters for almost thirty years and I wanted to meet her and Don. But, if I go to a party, I am a

wallflower. I was at a big thing recently with sixty other writers and hundreds of people. I knew a few people but I'm very

uncomfortable in those situations because if a friend walks away to go talk to somebody else I'm sort of stuck there. If I'm

introduced I can talk to somebody with some semblance of social skills, perhaps a tad bit of grace, but I'm actually very shy.

I like hanging out with funny people, but when it comes down to being serious, you have to do business - you got to make a living

and take care of your kids. There's a time to be serious, but I can have fun doing serious things. Here's something that's so

serious and because I'm certain I would have failed miserably at it, I think it's hilarious. When I graduated from Georgia State,

the thing I wanted to do in addition to writing was join the FBI. Since I was a kid, I wanted to be an FBI field agent. On my own

I'd been training and could exceed the requirement to the physical fitness training. I don't remember the requirements, but I

whatever they were I could do it all, two or three times beyond the requirements. If you had to do 30 pushups, I could do 100.

I got to the point where I could do 75 pushups in one minute - I'm talking real Marine pushups. I trained and was in solid

condition, but didn't tell any of my family about this. I did it on my own. My fastest mile was five-minutes flat, and I

regularly ran it in about five and a half minutes. I also trained to hold my breath underwater, everyday in the pool. My best

time, by slowing my heart rate and level of body activity, was three minutes and thirty-five seconds under water. Anyway, I filled

out the FBI application and was ready to mail it in when I read the last requirement wherein all of my hopes and dreams were dashed.

As a field agent you cannot be color blind. I just couldn't believe it. The end.

ROBERTS: There wasn't anything else in the FBI that you wanted to do besides be a field agent?

WALSH: I didn't realize that. I was so naive. When I couldn't be a field agent I figured that's all there was. Why would

they want me otherwise? I was flawed. Damaged goods. It never occurred to me that there were forensic specialists or computer

specialists. It never crossed my mind. The only other thing I might have been good at is being a sniper. As an investigator,

I have since been able to train myself to sit on surveillance or in position for up to eighteen hours without moving. Instead,

I decided to be a poet. In retrospect I don't know how successful I would have been in the FBI because I have a real problem with

authority figures, people telling me what to do, how to do it, and when to do it. That doesn't go over well in the FBI.

I really don't like authority. That's one reason I never went into the military. They don't have a program for a guy who

wants to "kind of" do it their way.

ROBERTS: How autobiographical is your work? Did you drive naked from Atlanta to Memphis as in the poem,

"In Anticipation of Spending Several Nights in Jail"?

WALSH: I almost never write about myself. The I in my poems is a fictional person, not me. Driving naked in the car really is a

metaphor for basically putting yourself out there, exposing yourself to whatever in your life causes you (not me) to be vulnerable.

However, in that particular poem, the girl is real, Becky Palmer, a girl I had an absolute crush on in high school. I wanted to say

to this young girl (now older, of course) how I felt all those years ago. I had literally said only one word to her in my entire

life - I was so shy I couldn't talk to her. I saw her every day in school for three years and could not say a single word to her.

She was a sophomore when I was a senior and on the last day of school, that afternoon, I pulled the car into the parking lot in

front of the school and there she was standing on the school steps alone. Not a soul around. As I walked up the stairs we looked

at each other, and I said, "Hi" and she said "Hi" back to me. I went in the school thinking "Wow, I did it. Maybe I can ask her

to the movies." Three minutes later when I exited the school, she was gone. The whole point of that story is the backdrop to the

poem. I needed a vehicle by which I could say to Becky Palmer, "Twenty years ago, I fell in love with you." I have never seen her

again since that day in school. So the poem's narrator years later drives naked from Atlanta to Memphis. Being naked is funny

because maybe he really drove naked in a stolen Corvette, but the nakedness is all of us being naked to the world. By saying to

her, I loved you once a long time ago, that puts the narrator out there in a vulnerable position. But let's be very honest. In

this instance, it's me very much exposed to the elements of emotion, because there is the chance she might call me up saying "I never

liked you and thought you were some brand of farm animal. I wouldn't have dated you, ever!"

I needed a vehicle to expose these emotions. So how do you write that? You start by making the narrator a fictional character with

a neighbor who owes a 1957 Corvette, which the narrator steals. From there anything was possible. At that point I removed myself

out of the emotional equation. Then I simply wrote a poem about a married guy with kids who leaves it all behind to chase the fantasy

of his youth, driving naked to tell a grown woman that one golden summer he fell in love with her. Ultimately, he ends up in jail,

hoping she remembers him because she needs to bail him out. It's all a metaphor. For the most part, I don't write autobiographically.

I take autobiographical snippets then find whatever it is I want to say and use those snippets for the bigger picture.

In Anticipation of Spending Several Nights in Jail

I opened the window this morning after a hot shower

and the neighborhood air rushed in against my skin.

My neighbor, Jerry, scuttled to the edge of his grass

for the newspaper, puttered around his manicured lawn

as he sucked down a Bloody Mary, chomping the celery

like it's the only thing in the entire world left to eat

and someone on a hang glider might swoop down

like a giant ferocious owl and steal it. "Hey Jerry!" I yelled,

"I don't wear pajamas." I figured he doesn't wear pajamas,

just waltzes around the house like Hugh Hefner

puffing a stogie, calls his bookie to drop a grand

on the Cowboys. Jerry's an out-of-shape scratch golfer

on his third wife. He writes a daily sports column for the Post Courier,

invites me over for summer cocktails and cookouts

with his friends, who, like him, wear brown fedoras

and are married to blondes named Doll

or Bunny. He listens to Dizzy Gillespe records.

His shirt reads, "Babe-a-holic" and his friends laugh

a lot at him for his horny-jerk self. But on this morning

the sun screamed off the chrome of his '57 Corvette, a forty-seven

year-old red dream I want to joy ride, just like that girl

in high school, just one spin around the block, the dream girl

who was always so golden that no matter who you ended up loving,

she was the one all women are compared to - how you watched her

cheerleader moves, the air and sunlight dancing around her

like time and space were invented for her body. But you never

spoke to her because you were some brand of farm animal.

Maybe she was so golden that one single word spoken to her

would have imploded the known universe. How many years

has it been since you saw her? Wherever she is today,

she's still golden, still wrapped in blue jeans, sparkling

white sneakers, some guy's football jacket draped over her shoulders.

She isn't gone. She's always there, ringing in your ears, forever,

like the thickness of air when glass shatters into silence.

I've decided, tonight, I'm going to steal Jerry's Corvette,

roll it quietly down the street, pop the clutch

at the bottom of the hill and laugh with the engine's roar

for balance and my obsession with unity.

Maybe I mean nudity. Me and his car. Naked as I drive

searching for the golden girl. It takes awhile,

enough time must pass to extinguish the fear, to say what

you longed to say, tell everyone who knows a girl like

Becky Palmer in Southaven, Mississippi, "One day

a long time ago, one golden summer, I fell in love

with you." Shouldn't the world know and shouldn't Becky know, too,

if for no other reason than to explain the theft

of Jerry's Corvette and driving naked from Atlanta to Memphis,

and why so many years later I would be calling her from jail.

ROBERTS: Who were your influences?

WALSH: First and foremost, David Bottoms. More so than most other writers. He was the beginning, and without having him as a

teacher, I may have never gone forward. In grad school, Jack Myers, who recently died. I may never meet another poet with more

patience than Jack. He was great and I needed a poet like him to crack my shell open. I've read a lot of fiction and non-fiction,

so I've been influence by that, too. When you first start writing you get an anthology and read it and are influenced by many poets.

You filter poets out by virtue of your tastes. I like that process. I remember reading the Beat Poets, A.R. Ammons,

James Dickey, W.S. Merwin. "For the Anniversary of My Death" simply floored me and I think is the most brilliant poem written

in the 20th century. I love that poem. Sharon Olds. Stephen Dunn. Robert Hass. I read all of Roethke and Hugo, studied all

aspects of their work and life. Jack Myers studied with Hugo at Iowa, and Hugo studied with Roethke. I love the idea of that

poetic dna running through my blood. There are too many writers to name, but once you go through these anthologies and see what

other poets are doing and after you finish stealing from them, you begin to find your own voice, filtering the wheat from the chafe

in your own work. Although it happens early for some poets, it was a long process for me. I don't know how I would have done it

more quickly. You get there at your own pace, but it's wrought with all sorts of stumbling blocks.

ROBERTS: How did you begin interviewing writers?

WALSH: As an undergrad, I went to a literary festival in Athens, Georgia and late that night got mildly drunk at the 40-Watt

Club and fell asleep in my car in a parking lot. About three in the morning I woke up to voices. Now the parking lot was completely

empty except for the cops arresting a guy up against my car. He was handcuffed. I quietly eased back down and when the cops took

him to jail, I took off because I was nervous. I drove all the way back to Atlanta, just wired. At home, I stayed up reading

Phillip Lee Williams' debut novel, The Heart of a Distant Forest and I didn't stop until I had finished. It so influenced me that

I just had to meet him. About six months later I interviewed him for a magazine. That Christmas, my girlfriend at the time, bought

me a tape recorder and said, "This is for your other interviews." She saw something because it never dawned on me to conduct

any others.

The next interview was with David Bottoms for the school magazine. I did a bunch more: Fred Chappell, Harry Crews, Lee Smith,

Doris Betts, Donald Justice, and then I wanted to interview James Dickey. I really felt that I needed some credentials before

asking him, not that the other writers were scabs, but in my mind asking Dickey for an interview was like asking God for the time

of day. He and Bottoms were good friends, so I just called Dickey up at his house. We talked for a few minutes then a couple of

days later he called me at home to say yes. Dickey probably called Bottoms to ask about this nutty college student calling him --

I'm sure through David's recommendation I got the Dickey interview. Once I interviewed Dickey, my credibility among the rest of the

literary world grew and there was no one I couldn't call. I've since interviewed Nobel Laureates Czeslaw Milosz and Joseph Brodsky,

as well as a host of named people. Talk about funny-A.R. Ammons was witty and had me laughing. He was one of the most enjoyable poets

I'd every met. I've thoroughly enjoyed the interview process and meeting all these writers because it forced me to be more

professional.

ROBERTS: Do you have specific favorite poems?

WALSH: My own poems? No, I'm tired of them all. I'm very excited about is the new poems I've written. You hear poets talk about

how tired they are of their poems - that's where I am. I cannot imagine what it's like to be Mick Jagger singing "Satisfaction" at

age sixty. Didn't Dylan Thomas read other poet's poems when asked to read? That's the way to do it. Read a few of your own, then a

few of your favorites by other poets.

ROBERTS: Are there people out there making a living as a poet?

WALSH: I think so. Not many, but some. Most people who are poets don't make a living at it. Most of them teach. I write poetry

because I like to. It's an art that I enjoy, just as if a person enjoyed the clarinet. I like playing around with sounds and

narrative, sculpting the poem. Look at William Carlos Williams and John Stone-they were doctors, or Wallace Stevens, the Vice-President

of the Hartford Insurance company. . . a lot of poets have occupations removed from teaching. They didn't make a living at it and it

doesn't seem to have negatively affected them. I like that diversity. Of the more contemporary poets, Rafael Campo is a doctor, as is

Roy Jacobstein. I like being able to have literature and writing be my sanctuary, a place to go where I can synthesize the events of

the world into some coherent matter. As an investigator, I see so much crime and mankind at its lowest point - I like to leave it

behind. I do the stuff I have to do to make a living, to keep the wolves off the front porch, but poetry is a sanctuary where it's

my own little world uninterrupted by most outside forces. Each of us must find that balance, and no one else will do it for you,

unless you are in the penal system, then you will march to their drum beat. Of course, who among us dreams of that situation?

ROBERTS: How'd you become an investigator?

WALSH: Boredom and necessity. I just needed a change and without much forethought dove into it. Surprisingly, I was good at it

from the get go. It's not much different than researching term papers. An investigation is really all research, the process of it.

When I'm tracking some guy across the country, it's just research. Well, that's all I did as an English major, research. I get to

work alone and occasionally the pay off is making some guy's life a living hell. That's funny in a demented way. The money is good,

but I would stop in a heartbeat for a full-time teaching position. Money is nice, but it becomes overrated when you are not doing the

thing you absolutely love doing, such as teaching.

ROBERTS: Do your children read your work?

WALSH: No, they're a little young, but aware of what I do. They are actually very proud of the fact that I write.

They tell strangers, taxi drivers, gas station attendants what I do. You see, I'm not yet the foil of their life.

I won't tell somebody that I'm a writer, but my boys have no problem propping me up against the wall to face the

firing squad.

ROBERTS: This is probably not the right place to ask this. Aspirations - what if you were rich or famous as an artist, as a poet?

WALSH: I think it was Billie Holiday who said that she's been poor and she's been rich, and rich is a hell of a lot better.

I have been incredibly poor in my life, absolutely no money and not knowing where anything was coming from. And as human creatures,

we like being comfortable. At this point of my life, I make a good living. My wife makes a good living. We're comfortable. But when

you talk about rich, movie star rich, hell, who wouldn't want that? J.K. Rowlings is worth a billion dollars. I can't image what

that would be like. The other day, I saw a 1967 Corvette 427, completely restored and listed for $249,000. If I had the money, I'd

write the check, but I've not been fortunate enough to have that kind of wealth bestowed upon me. But I'm not worried about it. My

wife and I talked about this about a month ago when the lottery was more than 250 million dollars. We never play the lottery, but if

we were to win we would start a foundation to help children read. Elaine is on the board of several charities, and the fact is, if a

child does not learn to read by the third grade, as a society, we have lost them. There is a 95% chance they will end up in jail.

This is a reprehensible statistic. I'd give a boat load of money to teach children to read, if nothing else since government schools

are failing to accomplish this. From there, all things are possible. Of course, our education system simply sucks and too many

children are ignored and fall through the cracks. A good education is like a rising tide - it lifts all boats.

ROBERTS: Money always seems to be the indication of success.

WALSH: Paris Hilton - Best-selling Author! That's my four word rebuttal. I prefer critical success. If my books don't sell

but I have critical success, I'll feel good. All my books have had great reviews. I mean, my book of interviews had major reviews

in newspapers that said wonderful things. I was happy. It was recently called a "classic." Wow. That feels great. Who could have

ever imagined that?

ROBERTS: The good reviews didn't necessarily translate into sales, per se

WALSH: I had decent sales. I didn't get rich, but I'm fine with that. The reviews were good and I was very pleased. I'd love to

sell a lot, certainly. But truthfully, the thing I like doing is raising my children. I want my kids to have a great childhood - teach

them things they need to know. Money - I don't worry about feeding my children each night, but some people are burdened with that.

That has to be very difficult. There are greater things to worry about than book sales. I really respect the man or woman out there

busting their ass every day trying to make sure there's food on the table for their children. For a lot of people it's difficult. I

am appalled by people who are just lazy and don't work and don't get out there - they make bad decisions and fail to do the things needed

to care for their children. In my business, I see it all the time. So many people are lazy and want someone else to take care of them.

It boggles the mind. But the person who is out there trying hard, working hard, making sure their children have what they need for a good

childhood and to maintain a structured home environment, I absolutely respect that. My uncle told me that your children will never

remember the things you buy them, but they will always remember the things you do with them. That is very true. I like spending time

with my children and if I sell fewer books because of it, c'est le vie.

ROBERTS: I agree and I never thought I would feel that way before I had children.

WALSH: The line in The Conscience of My Other Being that summarizes my life, "I wish I could help him/ understand that they have

made me a better man/ than I could have ever hoped or dreamt to have been on my own." That is the truth. My children made me a

better person. When you're not married and don't have kids, you're just out doing whatever you want, hanging out with buddies,

drinking, going to ball games, trying to get laid, all that fun stuff. But after awhile it becomes stale; however, you don't realize

it until later when you have children. Children force you to become a better person. Most people. Not everybody. Certainly for me.

Children force you to grow up and stop whooping and hollering at two in the morning. There is, of course, always Las Vegas! The

irony is that all my single friends want to find the love of their life, while my married friends are having affairs!

ROBERTS: You were born in Jamestown, NY and as you said, moved around a lot. You ended up in the South and have lived in

Atlanta for thirty years. Do you identify yourself as a Southern writer?

WALSH: At this point, yes. I'd like to say I'm a Southerner, but it's a tough distinction. When I think of home I think of

my grandfather's house in Lakewood, NY, a little town on Chautauqua Lake a few miles outside of Jamestown. That's the only

stable house of my childhood. He lived there for more than fifty years. My ancestors on my mother's side of the family have been

there since before the Revolutionary War and fought in that war. They also fought for the Union Army in the Civil War and worked

with the Underground Railroad. My father's side has been in that area since the 1840's and they, too, fought in the Civil War.

My mom's mother grew up and was good friends with Lucille Ball, who lived in Celeron.

ROBERTS: Did you meet Lucille Ball?

WALSH: No, but she was the subject of great family lore. My grandmother died when my mother was seventeen so I never met her,

but she and Lucille Ball were good friends. As a kid, I lived a few blocks from Natalie Merchant, although I never met her. My cousin,

Heidi, is best friends with the actress and comedian Laura Kightlinger, who is from Jamestown. And, Steven Corey, the editor of the

Georgia Review, lived not too far from me but we were separated by eleven years so we never knew each other until later in life.

That area is home but I've been away so long that. . . it's still home. . . when in my mind's eye I think back. I'm just a visitor,

an interloper in the South. My children are Southerners, as is my wife, who is from Greenville, SC.

ROBERTS: Do you feel a sense of being a Southern?

WALSH: At times, I do. I've been in the South so long all of the influences of the region filter in to my subconscious. But, in

reality, Atlanta is no more the South than Chicago. It really isn't. It's a very beautiful city and there are southern things but

it's not the South. I discovered this a few years ago when we drove up to Washington, D.C. for vacation. I felt a greater sense of

southern history driving through North Carolina and Virginia, being in the middle of nowhere, in a place where some great Civil

War event had occurred. In Georgia, I can find the south, but it's not in Atlanta. It's thirty to forty miles away in any direction.

Atlanta does not feel southern to me, not in the way a small town does-it's just a big metropolitan area, like Dallas or Chicago - they

have their nuances, quirks, foods, language and accents, but it doesn't feel like the south as when I go to Crawford, GA to visit Marion

Montgomery and his wife. Atlanta is just another big city. I mean, look where we are, sitting outside Starbucks. If you took down the

signs you might think you were in Tucson. Or Pittsburgh or Cincinnati. You wouldn't know the difference. Look around - what do we

see: Starbucks, Smoothie King, Athlete's Foot, Kroger, Goodwill, Petsmart. Is there one thing here that's not corporate? You can't

find one thing here that's southern. We could be in L.A., Seattle, or Kansas City. It's all pretty boring if you ask me. If I drive

to Valdosta I sense the south as long as I'm not on the interstate. I'm not lamenting any of this. I'm simply stating this as fact.

I like Atlanta, and I like big cities, too, but distinct culture, with the exception of New York City, is not in the cities, in my opinion.

It's too homogonous.

ROBERTS: Do you have your early poems from college and do you ever look at them?

WALSH: No, in fact, all the poems I wrote for my college girlfriend, after our relationship dissolved years ago, I shredded. I needed

a catharsis to get her out of my mind. To purge myself, I shredded our life together, every aspect - poems, letters, notes, photographs,

you name it. I sat at the shredder one day and just said goodbye.

ROBERTS: If you looked at those old poems now would you see anything good, at least one line?

WALSH: Honestly, the poems were not very good. So, probably not. What good has come from it is the emotional reference point from

which I can draw upon if need be. About five or six years ago, I found tucked in a book a 20-year-old letter from her to me after one

of our breakups, a very nice, heartfelt letter. I read it and could still hear her voice in those words. That was nice. By that time,

though, I had been married for a while and had moved on. I shredded it.

ROBERTS: Did the catharsis work?

WALSH: It's hard to say. I'm not the same person I was at the time. That guy probably might still be broken up over her. But,

this guy isn't. I've moved on with my life and married a woman who is quite wonderful, smart, and motivated. She's a Duke grad and

Emory law grad. We have three beautiful children, and at times she laughs at my stupid jokes. So it has all worked out very nicely.

But in regard to the catharsis, I had to let her go, but still, not a day goes by that I don't think of her in some nice way, as I do

with most old friends. I wrote a poem about her, "Turning Towards White." But if you're asking me to be honest with you-the catharsis

probably did not completely work.

ROBERTS: You've mentioned to me that you have letters from all sorts of writers, including Donald Justice, Milosz, and Eudora Welty.

What kind of letters from Eudora Welty?

WALSH: I wrote her about something years ago and she wrote me back. I had just stacks of letters from famous writers.

I shredded all that, too. Not just the former girl friend's letters. Walker Percy. A.R. Ammons. You name it. The only

one I kept was from Robert Penn Warren. I still have that.

ROBERTS: Why did you shred them?

WALSH: I'm not a packrat and I have this minimalistic lifestyle where I don't horde stuff and if I don't use it. . . .

ROBERTS: Even about yourself? Do you keep reviews of your book?

WALSH: I don't keep that stuff? I have no need for it. I used to keep all sorts of stuff-boxes and boxes of stuff, just so

much STUFF. I shredded everything. If somebody autographs a book for me, I keep it. I have a first edition copy of

Alnilam by Dickey that he inscribed to me. I think it's a brilliant novel.

ROBERTS: Even for your kids? One day they'll look back and think you were cool.

WALSH: Once your children reach age thirteen, there's nothing you can do in this entire world that they will think is cool.

One of the best ways to be a great dad to your kids is to not burden them with your ghosts! I'm trying my best to

keep up my end of that deal.

If you would like to be added to my monthly e-mail newsletter, which gives information on readings,

book signings, contests, workshops, and other related topics...

To subscribe to the newsletter send an email to:

newsletter@cervenabarvapress.com

with "newsletter" or "subscribe" in the subject line.

To unsubscribe from the newsletter send an email to:

unsubscribenewsletter@cervenabarvapress.com

with "unsubscribe" in the subject line.

Index |

Bookstore |

Gallery |

Submissions |

Newsletter |

Interviews |

Readings |

Workshops |

Fundraising |

Contact |

Links

Copyright © 2005-2011 ČERVENÁ BARVA PRESS - All

Rights Reserved

|